The Enigma of Ur

Is the music of the future one in which form and structure give way to an aesthetic inspired by the primordial?

The American arts are receding and blurring. Cultural memory—a prerequisite—is fast disappearing. American orchestras, espousing the new, privilege a surfeit of makeshift eclectic music dangerously eschewing lineage. American opera companies flaunt new American operas that are here today and gone tomorrow. What is needed is an informed quest for orientation, for future direction.

The Italian-born composer-pianist Ferruccio Busoni was a clairvoyant who will never cease to magnetize a coterie of adherents. In his Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music (1907), Busoni proposed the notion of “Ur-Musik.” It is an elemental realm of absolute music in which composers have approached the “true nature of music” by discarding traditional templates. Sonata form, since the times of Haydn and Mozart a basic organizing principle governed by goal-directed harmonies, would be no more.

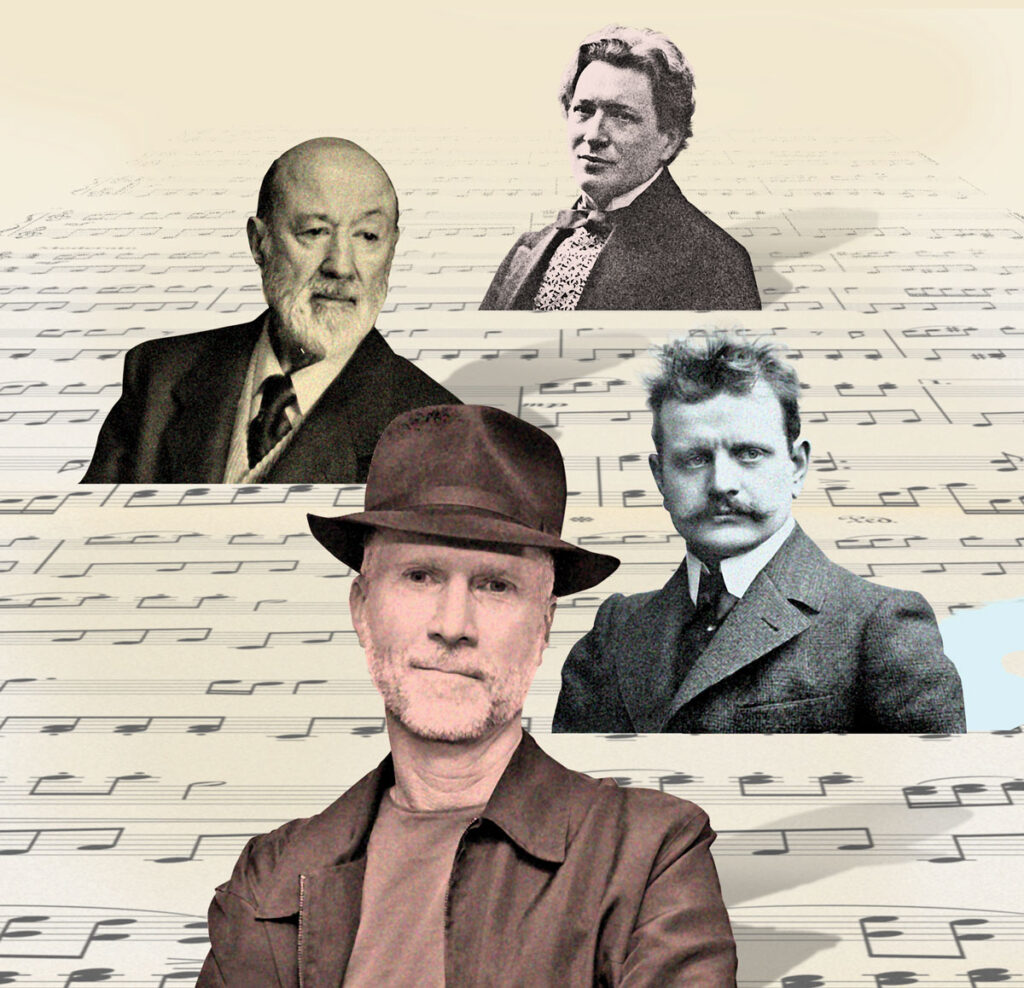

Half a century ago, Ur-Musik could be written off as a faint footnote to twin seminal 20th-century currents: Igor Stravinsky’s neoclassicism and Arnold Schoenberg’s serial rigor. But no longer. John Luther Adams, among the most esteemed present-day American composers for orchestra, embraces something like it. And his forebears include composers of renewed consequence: Jean Sibelius in his primordial tone poem Tapiola (1926) and Charles Ives in his unfinished Universe Symphony (begun in 1915).

Around the same time, before locking on his 12-tone rows, Schoenberg experimented with an unmoored nontonal style. He was concurrently corresponding with Busoni, who also conferred with Sibelius. In an email exchange, I learned from Adams that, while composing his Pulitzer Prize–winning Become Ocean (2013), “the only music I was listening to was Tapiola.” I brought up Ives’s Universe Symphony and suggested that Adams was “post-Ivesian.” He readily agreed. So there are dots—big ones—to connect.

Might there not be lineage here?

The story of John Luther Adams will become increasingly familiar as his music continues to penetrate our recalcitrant concert halls. Now more than 70 years old, he is very much a phenomenon of the present day—and yet anchored in sediments ages older than academia or the concert hall.

Born in Mississippi, he was a rock drummer who habituated Greenwich Village as a teenager. He graduated from the California Institute for the Arts and became a farmhand in Georgia. He moved to Alaska in 1978 and worked for the Northern Alaska Environmental Center before turning exclusively to music. As timpanist for the Fairbanks Symphony, he was privileged to inhabit the symphonic canon—but only after his creative bearings were fixed. The tragedy of Alaska wildfires drove him to the southwestern United States, where he now resides.

Encountering Adams’s Become Ocean on a 21st-century symphonic program is so fundamentally enthralling that it risks cliché. It is the proverbial oasis in the desert. The Sahara here is contemporary American concert music inscribed in sand. The ocean Adams supplies is equally physical and metaphysical. Its tides heave and recede. In place of tunes, it proposes shifting modulations of texture, pulse, and harmony. The harmonies are triadic but barely directional; they shimmer atop anchoring brass choirs. Two listening planes are volunteered: The grateful ear can track harmony and structure or relax into near stasis, but the stasis is not decorative or sybaritic. This water has teeth. Art conceals art. The latent organization (I have read) invokes fractals, chaos theory, waveforms. The entire 45-minute span describes a palindrome. A composer’s note explains the title: “Life on this earth first emerged from the sea. And as the polar ice melts and sea level rises, we humans find ourselves facing the prospect that once again we may quite literally become ocean.” There is also this preliminary instruction marked in the score: “inexorable.”

In the excitement of discovery, the listener asks, From where does Become Ocean arise? And where might it lead? Is Adams an inspired epiphenomenon? The question nags because we have lost our musical bearings in a flood as superficial as Adams is not.

In 1925, on the first anniversary of the death of Ferruccio Busoni, his former pupil Kurt Weill wrote: “I will never forget the feeling of relief which we experienced when, in 1920, after an absence of six years, Busoni returned to Berlin. … He came like a fresh gust of air. He was able to transcend the distortions in which we had sought escape. … It is strange enough that such a phenomenon appeared in our time. Even in the past we find few figures in whom the man and the work are thus unified. … We are bound to think of Leonardo.”

Few musicians in the Western tradition have inspired such paeans of reverence and gratitude. Weill’s allusion to da Vinci fits: Busoni’s wisdom was both practical and strange. His pupils also included Edgard Varèse, who fed on Busoni’s exposition of musical “essence.” So it was, as well, with Sibelius. The performers who revered Busoni were legion. Joseph Szigeti and Dimitri Mitropoulos were two of the most famous to insist on his compositional legacy. I myself happened to know Claudio Arrau, who—like Rudolf Serkin, Adolf Busch, Artur Schnabel, and countless others—heard Busoni perform in Berlin. Remembering that, Arrau was stunned into bewildered admiration. In our conversations, he surveyed a procession of great Berlin names. He did not recall anyone else in quite the same way.

Processing Become Ocean, I find myself asking: What might Busoni teach us today? When he writes that Ludwig van Beethoven “did not quite reach Ur-Musik, but in certain moments he divined it, as in the introduction to the fugue of the Hammerklavier Sonata,” we instantly glean what he is dreaming about. Beethoven here conceives astral music, in which the particles of the fugue to come are as yet untamed. They mysteriously inhabit a swirling cosmos. They are elemental, preternatural.

Busoni continues: “Indeed, all composers have drawn nearest the true nature of music in preparatory and intermediary passages (preludes and transitions), where they felt at liberty to disregard symmetrical portions, and unconsciously drew free breath.” Busoni here references Bach’s organ fantasias (“but not the Fugues”) and the transitions to the finales in Robert Schumann’s Fourth Symphony and Johannes Brahms’s First. And there is a counterexample: “Is it not singular, to demand of a composer originality in all things, and to forbid it as regards form? No wonder that, once he becomes original, he is accused of ‘formlessness.’ Mozart! The seeker and the finder, the great man with the childlike heart—it is he we marvel at, to whom we are devoted; but not his Tonic and Dominant, his Developments and Codas.”

Assaying the “essence” of music—its basic, primordial identity—and juxtaposing that with other forms of artistic expression, Busoni writes: “It touches not the earth with its feet. It knows no law of gravitation. It is wellnigh incorporeal. Its material is transparent. It is sonorous air, it is almost Nature herself. It is—free.” This conviction is another version of an idea familiar in 19th-century Germanic thought: Schopenhauer was an especially influential apostle for music as the deepest creative mode, unfettered by language or visual representation. In Busoni, it drives a veritable credo:

Music was born free; and to win freedom is its destiny. It will become the most complete of all reflexes of Nature by reason of its untrammeled immateriality. Even the poetic word ranks lower in point of incorporealness. It can gather together and disperse, can be motionless repose or wildest tempestuosity; it has the extremest heights perceptible to man—what other art has these?

Yet the same “free breath,” drawn “unconsciously,” animates Wassily Kandinsky’s first excursions in nonrepresentational visual art as well as Arnold Schoenberg’s first attempts at nontonal music. Kandinsky and Schoenberg discussed their common purpose in a famous exchange of letters. It should not then surprise us that Schoenberg and Busoni also corresponded (less famously) in a span of letters (1903–1914) that contains this characteristic Busoni sally: “Maybe I, some later Siegfried, shall succeed in penetrating the fiery barrier which makes your work inaccessible, and in awakening it from its slumber of unperformedness.” The common ground they evince, in Busoni’s words, compasses “pure, unspecified, refined ideas for the piano, sound without technique.” Schoenberg calls it “unshackled flexibility of form uninhibited by ‘logic.’ ” In the same letter, he disavows “harmony as cement or bricks of a building,” “protracted ten-ton scores,” and “Pathos!”

But, as I said: I believe in actual fact that you are wrong.”

Not the least fascinating aspect of this dialogue is its self-portraiture, juxtaposing Busoni’s complex urbanity with Schoenberg’s extremism of sentiment and opinion, as when he insists on envisioning a subconscious music snared on the fly before his mind corrupts it: “This is my vision: this is how I imagine music before I notate = transcribe it. And I am unable to force this upon myself; I must wait until a piece comes out of its own accord in the way I have envisaged. … My only intention is to have no intentions!”

Schoenberg next sends Busoni a pair of pathbreaking nontonal piano pieces from his Op. 11 (1909). Busoni is full of admiration. He imperturbably adds: “My impression as a pianist, which I cannot overlook … is otherwise. My first qualification of your music ‘as a piano piece’ is the limited range of the textures. … As I fear I might be misunderstood, I am taking the liberty—in my own defense—of appending a small illustration.” Busoni takes a measure of Schoenberg’s piano writing and “enhances” it. He continues (and we here glimpse Busoni the pedagogue): “This is neither intended as judgment nor as criticism—to neither of which I would presume, but simply a record of the impression made and of my opinion as a pianist.”

Schoenberg: “I have considered your reservations about my piano style at length. … It seems to me that particularly these two pieces, whose somber, compressed colors are a constituent feature, would not stand a texture whose effect on one’s tonal palate was all too flattering.”

Busoni: “I have occupied myself further with your pieces, and the one in 12/8 time [No. 2] appealed to me more and more. I believe I have grasped it completely. … Although I have become completely at one with the content, the form of expressing it on the piano has remained inadequate to me. To complete my confession, let me tell you that I have (with total lack of modesty) ‘rescored’ your piece. Although this remains my own business, I should not fail to inform you, even at the risk of your being annoyed with me.”

A connoisseur at taking offense, Schoenberg next responds: “Above all, you are certainly doing me an injustice. … My trust absolutely cannot be shaken by this divergence. On the contrary, it has increased since I personally came in contact with you. The intuition I already had about the nature of your personality has been confirmed. And now I have formed a fairly clear picture. I can perceive a facet of your personality that is infinitely valuable to me: the endeavor to be just! And I value this endeavor higher than justice itself. … Therefore, even if you are in fact doing me an injustice, nothing in the world could give me greater pleasure than the way in which you do so. But, as I said: I believe in actual fact that you are wrong.”

Busoni: “Your last letter is an interesting document, which I value very highly. … Happily we have struck an attitude of frankness to one another, and I would ask: to what extent do you realize these intentions? And how much is instinctive, and how much is ‘deliberate?’ ” And that is the nub. In tandem with the Op. 11, No. 1, the seven-minute piano cameo in question records Schoenberg abandoning the last vestiges of tonality. Its expressionist temper is lugubriously moody. A rocking ostinato anchors the outer sections. Atop, Schoenberg limns lyric aches and pains. (Busoni’s more pianistic version is less stark; it summons a sonorous void echoing with tinted sonic tendrils.) And yet at the same time, the piece does evoke something akin to “pure feeling”—an unfettered, improvisatory expressive impulse.

About a dozen years later, Schoenberg decided he could not proceed without some theoretical grounding and created his 12-tone system. Did this practice of “serial technique” obviate Ur-Musik? It should have. And yet, since the system does not work—notwithstanding the sequence of ordered rows, we readily experience such music as directionless—there exist 12-tone exercises evoking Busoni’s incorporeal freedoms. I am thinking, for instance, of certain passages in Schoenberg’s opera Moses und Aron (1932) in which a biblical desert landscape, suffused with divinity, inspires music sounding primordial and elemental not because but in spite of its abstruse methodology.

And there may be a whiff of Ur-Musik, as well, in Schoenberg’s antipode Igor Stravinsky: the primal intensities of The Rite of Spring (1913) and Les Noces (1923), the frozen codas of Apollo (1928) and The Fairy’s Kiss (1928).

No Busoni overview is simple. He was born in Empoli in 1866. His father was a nomadic Italian clarinet virtuoso out of Fellini. His mother’s lineage was German and Jewish. No less than Gustav Mahler (who esteemed him), he embodies qualities of paradox and irony both implicit and manifest. His Faustian striving is oddly leavened by espousals of Mediterranean clarity and proportion. Busoni the pianist was famously regarded as a successor to Franz Liszt, whom he both resembles and contradicts. His core keyboard affinities—a singular list—were for Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and Liszt. In his own compositions, every Busoni paradox is in play. The best-known early Busoni is the Sonata No. 2 for Violin and Piano (1898) and the five-movement, 70-minute Piano Concerto with chorus (1904). The Ur-sensibility of his riper music is here more than nascent, but the scale and weight are Romantic. Late Busoni tacks toward Ur-Musik and—another label from his aphoristic writings—“Young Classicism.” That those two concepts seem contradictory is a typical Busoni ambiguity. The latter overlaps but does not describe neoclassical restraint. Late Busoni renounces the “sensuous” and also Germanic Innerlichkeit (“inwardness”) in pursuit of a “re-conquest of serenity.” The harmonic language is subtle and original.

Busoni’s peak achievements for solo piano include a 14-minute Toccata (1921) launched by 39 measures of cascading arpeggios marked forte and Quasi Presto, arditamente. That this Ur event, an astral storm equally tempestuous and impersonal, cannot possibly be rendered “staccatissimo” (as prescribed) is pregnant: the unplayable evinces the unknowable. The opera Doktor Faust, begun in 1916 to his own German libretto, is Busoni’s summa. He did not live to complete it. Its pivotal Sarabande—a vaporous symphonic interlude—is a Busoni litmus test: If you succumb to its “peculiar serenity” (the critic Paul Bekker’s 1924 term for the Busoni affect), you are hooked.

Late Busoni also embraces the musical legacy of a few years in the United States (1891–94), where he taught and also toured widely. His letters document estrangement from the New World, including a 1911 summation distressingly pertinent today: “My opinion of [the United States] has once again changed remarkably. Not only do I hold no brief for its cultural ascent but I also believe it has already passed its zenith. What the Americans have done since crossing this line is leading to a moral desert.” He at all times made an exception for Native America, a magnet for his mystic bent and wide curiosity. In the combination of prairie vastness and shamanistic visions of the otherworldly, he discovered a “vibrating universe.” Touring in Ohio in 1910, he wrote to his wife:

I spoke to a Red Indian woman. She told me how her brother (a talented violinist) came to New York to try to make his way. “But he could not associate his ideas with the question of daily bread.” … Then she said that her tribe ought to have an instrument something like this: A hole should be dug in the earth and string stretched all around the edges of it. I said (in the spirit of the Red Indians): An instrument like that ought to be called “the voice of the Earth.”

Busoni’s aspiration (in Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music) to “express in well-defined form something of the infinity that surrounds human life” hence produced three “Indianist” compositions, of which the most ambitious is the Indian Fantasy for piano and orchestra (1914). Using Native American tunes furnished by his onetime student Natalie Curtis (an important early ethnomusicologist), Busoni here conjures “formless” landscapes wedded to elemental ceremony and song. Curtis attended the American premiere (performed by Busoni, Leopold Stokowski, and the Philadelphia Orchestra) and wrote, “The walls melted away, and I was in the West, filled again with that awing sense of vastness, of solitude, of immensity. … All this, the spirit of the real America (a spirit of primeval, latent power) Busoni had felt.”

It was Antonín Dvořák who ignited four decades of Indianist compositions inspired by Native American music and lore: a mountain of kitsch transcended by his New World Symphony (with its poetic allusions to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha), by Busoni, and by Arthur Farwell. Today dismissed as an “appropriator,” Farwell was a veritable ethnomusicologist. His astringent Navajo War Dance No. 2 (1904) for solo piano is the closest thing I know to an American idiom in parallel with Béla Bartók’s raw absorption of Transylvanian song and dance. Farwell’s Hako String Quartet (1922) is beautifully inspired by the frisson of a Pawnee ritual. But it is Busoni who wrestles with the enigma of Ur. In his mature output, it is omnipresent.

If Busoni’s correspondence with Schoenberg ultimately led nowhere, his personal and epistolary relationship with Jean Sibelius, who was pursuing a kindred Ur-Musik, was sustained. The ferocious Theodor Adorno, who polemically pitched Schoenberg, debunked Sibelius as a barbaric antipode. But Schoenberg and Sibelius are not necessarily strange bedfellows. At one time or another, they equally pursued the illusion of an elemental music that “composed itself.”

In 1888, Sibelius and Busoni met almost daily in Helsinki, commencing a relationship that lasted until 1921. In that year, Sibelius wrote to Busoni: “I thank you from the bottom of my heart. … Without you, the [fifth] symphony would have remained paper and an apparition from the forest.” Busoni promoted Sibelius via the indispensable concerts of new music he conducted, engaging the Berlin Philharmonic at his own expense (1902–1909); his programs also included Schoenberg. When one reads that Sibelius admired Busoni’s Berceuse élégiaque (1909), a picture snaps into place—it is a chiaroscuro in which timbre and color are as important as pitch or harmony, a poetic experiment in incorporeal darkness.

If Schoenberg’s Op. 11 records an Ur-Musik moment, for Sibelius the litmus test is his last major work: the 20-minute tone poem Tapiola. Here the forest spirit Tapio, pervading “Northland’s dusky forests” in the Kalevala legends, is conjured amid howling winds. But the presiding essence is interior. Richard Wagner, at the opening of Das Rheingold, attempts something comparable: The orchestra evokes both water music and the beginning of time. In his “Forest Murmurs” from Siegfried, we may intermittently hear the Forest Bird; otherwise, the trembling strings make audible what is in nature inherent and silent. In Tapiola, an existential vacancy is sustained. A gaping two-measure silence, early on, corroborates Busoni when he writes, “The rest and the pause are the elements which reveal most clearly the origins of music. … The spellbinding silence [becomes] music itself. It leaves more room for mystery.” A rocking motion registers timelessness, impersonal stamina, sheer inertia. The naked patches of tremolo, the long syncopated pedals in the brass, and the trembling timpani rolls (also syncopated—nature does not rumble on cue) depict a vast northern canvas. On this backdrop, Sibelius inscribes motivic shards arising from a core idea. They become topics in a grand project of coalescence. The tectonic plates—the chordal slabs and vibrating planes—shift and collide, striving for alignment. The climaxes are seismic, a vortex of mystery and terror. The effect is superhuman and suprahuman.

In Sibelius’s oeuvre, Tapiola is the final, ripest manifestation of his goal to suggest music discovering itself, an evolving aural terrain in parallel with Finnish nature, which he revered. In his diary, he recorded the changing seasons, the effects of light, the speaking silences of land, sky, and water indifferent to man. “I should like to compare the symphony to a river,” he wrote. “It is born from various rivulets that seek each other in the way the river proceeds wide and powerful to the sea.” He wanted “motives and ideas” to “decide their own form.” He aspired to quasi-intuitively discern an inner logic. “When I consider how musical forms are established I frequently think about the ice-ferns which, according to eternal laws, the frost makes into the most beautiful patterns.”

In late Sibelius, music can vanish. I am thinking especially of the Sixth Symphony, an elusive exercise in modal harmony whose first movement is suddenly and unceremoniously over, a moment laconic and weightless. It evokes nothing so much as the final measures of Busoni’s Indian Fantasy, in which the actors become ghosts and are at once no more. “In a picture, the illustration of a sunset ends with the frame; the limitless natural phenomenon is enclosed in quadrilateral bounds,” writes Busoni in The Essence of Music. Music “can fade away like the sunset glow itself … and awaken the same response as the processes in Nature.”

Unless the composer is John Cage, no music can actually remain unmanipulated. This illusion requires sleight of hand—like that of John Luther Adams.

Might such music be informed by Busoni’s egoless Ur-Musik ideal? I asked Adams in an email. He replied, “When I was young and living a hermetic life in my cabin in Alaska, I read Busoni’s Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music a couple of times. A lot of what he says resonated with me. But in those days it wasn’t easy to find recordings of much of his music. So, although I couldn’t begin to call him an influence, I did find him to be a kindred spirit.”

In his beautiful book Silences So Deep: Music, Solitude, Alaska (2020), Adams discloses a reverence and fascination for Indigenous drumming that recall Busoni and Native America. He also writes, “My primary musical family is American, extending back several generations.” He names 18 composers commonly grouped as “mavericks.” The most prominent include Edgard Varèse, Henry Cowell, Harry Partch, John Cage, Lou Harrison, Morton Feldman, Conlon Nancarrow, and—the oldest name—Charles Ives. This category obviously suits Adams, but it more describes an attitude than a style. Sibelius comes up on a shorter European list. And when Adams describes a pivotal nature epiphany, Sibelius’s Nordic nature diary leaps to mind: “My ear caught a faint tinkling—like glass wind chimes in a gentle breeze. Looking down, I realized it was meltwater, resonating from deep within a crevasse.”

The name that tinkles more than faintly, however, is the biggest, most protean, of the Americans. Because he was late discovered, because he was initially misread as a modernist, Ives remains a perpetual outlier in the American musical narrative. Still, Cowell and Harrison, on Adams’s list, were Ives acolytes. And the music Ives heard in his head—a diffuse memory cloud of tunes and sounds and ceremonies—is Ur-Musik no fastidious modernist would endorse. When Ives testified that he “hated music,” that he heard “something else,” he is broaching Busoni’s “new aesthetic.” And Ives, here resembling Sibelius and Adams, conjures an anchoring Nature both physical and metaphysical.

Early on, when still a student, Ives composed the song “Feldeinsamkeit” to a text once famously set by Brahms. He discovered in Hermann Allmers’s nature poem an “active tranquility,” versus Brahms’s “quietude.” Years later, in The Housatonic at Stockbridge, he created a layered nature portrait depicting water, mist, and a waterborne hymn tune. As in Adams’s Become Ocean, Claude Debussy and La mer are perhaps discernible influences. But, as in Become Ocean, Ives’s shifting textures are not Gallic: iridescent, pristine. Rather, they are of the New World: elemental. The Housatonic is to Ives and New England what Tapiola is to Sibelius and Finland. Subsequently, crowning the summit of his Fourth Symphony, the quivering Ives ether, its restless quiescence, grows ever more abstract. All of which points to a linchpin: Ives’s unfinished Universe Symphony. Shedding the memory cloud of church and parlor, of Connecticut cameos, it transitions toward something like Become Ocean. Might Ives thereby acquire belated progeny? This is how I came to ask John Luther Adams if he considered his music “post-Ivesian”—and earned a “yes.”

But does the Universe Symphony sufficiently exist? The Ives literature barely touches it. Larry Austin and Johnny Reinhard have created and recorded performing editions that have not nearly entered the Ives canon. Now, completing editorial work begun by the late David Porter, the Ives scholar and conductor James Sinclair has created a third version. And it is Sinclair’s advocacy of Ives’s Universe Symphony that got me thinking about Busoni and John Luther Adams.

The Ives-Sinclair Universe Symphony is 30 minutes long. Sinclair describes the idiom as Ives’s “ultimate expressive language, angular and abstract but emotional. It should be heard outdoors—people could wander through the sounds. Or via something like Dolby 5.1 quadraphonic sound—so sitting in a room you could experience it from different locations.” Ives himself wrote that he was “striving to … paint the creation, the mysterious beginnings of all things known through God and man, to trace with tonal imprints the vastness, the evolution of all life, in nature, of humanity from the great roots of life to the spiritual eternities.” He envisioned the Universe Symphony performed by orchestras situated in valleys, on hillsides and mountains, with the music mimicking “the planetary motion of the earth … the soaring lines of mountains and cliffs … deep ravines, sharp jagged edges of rock.” A percussion ensemble represents the eternal pulse of the universe.

During Ives’s creative decades—a span beginning in the 1890s and ending in the 1920s—many dismissed him as a crank. Today, his (and Sinclair’s) aspirations for an outdoor Universe Symphony don’t sound all that different from what John Luther Adams is attempting in a series of works beginning with Inuksuit, premiered by 18 percussionists at Canada’s Banff Centre in 2009. And Sinclair is certainly no crank—his series of Ives recordings, on the Naxos label, is a landmark endeavor. To date, he has managed to conduct the Universe Symphony only once—at the Aldeburgh Festival in England. He is itching to record it. Many an orchestra has embraced Become Ocean. The Universe Symphony deserves another shot.

Art all too often requires advocacy. Busoni responded with his new music concerts in Berlin, Schoenberg with his in Vienna.

In the United States, Leonard Bernstein, bucking fashion, mounted a sustained campaign for the 20th-century symphonies of Mahler, Ives, Carl Nielsen, Sibelius, and Dmitri Shostakovich.

Back in the 1990s, it was my good fortune to run the Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra—an institution that, both in fact and in spirit, no longer exists and that once served an audience likewise now extinct. Were that opportunity to miraculously rematerialize, I would choreograph an Ur-Musik festival juxtaposing Busoni, Sibelius, Ives, and Adams—and see what might happen. I actually know a few conductors who would be game to attempt something like that.

“I try to draw my music directly from the earth, as unmediated as possible by culture,” Adams writes in Silences So Deep. “A problem of the first magnitude is formulated with apparent simplicity, without giving the key to its final solution,” writes Busoni of the quest for music’s “unchangeable essence.” The problem “cannot be solved for generations—if at all.”